My grandfather (maternal, not the one I made the film about), was a tough man. He came from a background of mystical religiousness where money and assets were considered nothing but worldly matters, and modesty and piety was the real thing. He always aimed high in life: he married high, studied and worked high, raised and taught his children high, and built their life for them as high up as can be. While living alone in KSA, he seldom had anything but red tea and foul, and sent every penny home to his immediate and extended family. He regularly boasted about how all the other 3azaba (single men) laughed and danced the nights and the money away on drinking, while he stayed in his room reading. There was a story he kept telling us and we would later copy him saying it (bad little kids that we were), about his friend Tayoba (Altayeb) who returned after many years in the diaspora and visited him in his big, fancy new house in Alsafia:

|

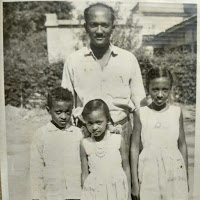

| My gramps in Juba sometime in the 1960s, my mum on the left, Mahasin and Mohamed (RIP) |

– Isam Eldin! (my gramps)

– Aywa! (yes!)

– Da beitak?? (is this your house?)

– Aywa! (yup!)

– Kollo?? (the whole thing?!)

– Aywa! (uhuh!)

– Fog ti7it? (from top to bottom?)

– Aywa! (you bet!)

And then, the best part: baka!! as the story ends with poor Tayoba bursting into tears mourning the years and money he wasted on nothing.

He travelled the country as a teacher and headmaster for boys’ schools, and his reign of terror was so fierce that somewhere in the South the boys nicknamed him ‘The Fireman’ because he walked a round with a stick oo fire, ushering the stray boys back into schools. There was no mucking around on his watch. Students and teachers were put and stayed in line. Education prospered. Everyone did their work. But it wasn’t just all tough-love: on his watch, no student was to be sent home, no matter what. Kids who were kicked out of schools in other regions were brought to him to take in. In his opinion, a boy out of school was a boy on the streets, with no future and no hope in life. Everyone had to have an education. Sometimes desperate mothers would even bring their boys to his house. The classrooms had a specific allowed number of registered students, and when the inspectors came, all the extra students that weren’t officially enrolled would escape out the windows, and when exams time came my grandfather would bluntly state that these kids had already made it this far so the system could not possibly prevent them from taking the exams. And back into the system they would go.

He was always mentioning some folan or another whom he had helped. I secretly didn’t believe most of it, but once my aunt came home from an errand at some government facility with him, and told us about a high-ranking official who walked past them as they were standing in line, then doubled back and came up to them, recognizing my grandfather. He then helped them through all the procedures and sent them on their way, telling my aunt how he had been kicked out of school as a kid and my grandfather had taken him into his school and pushed him through the year. Without Ustaz Isam Eldin, he said, I would have been lost.

I don’t remember him as a nice person. He was always so dry and iffy, turning off lights and fans and the television when we were watching cartoons. He kept opening the windows when there was a sandstorm outside. He didn’t like kids or housemaids or beggars, and his house was overflowing with them. He had this weird laugh that both Ahmeds could copy to the dot. He had several mottos for life that he would tell us:

Al7aya girsh! (life is about money)

Al3a6ifa cross! (say no to emotions)

Alshahada walshoghol! (your education and your job, i.e. marriage comes third, but when you marry, marry high)

He had one friend: Ahmed Shouna, whom he would visit almost every day, except when my grandmother told him not to go. He was always complaining of his knee and his ulcer, but refused to pray sitting in a chair until well after his mind was gone. He went to work as a judge after he retired from teaching, and sometimes told stories about how many criminals he had ordered whipped that day, and how the street kids got themselves arrested on purpose because jail was the only place where they had a meal and a roof over their heads, and how once 2 drunken women were caught and put in jail overnight, and when they were brought before him the next morning he told the bailiff to take them into the yard to watch the other criminals getting whipped, and they watched and cried out in terror and begged for mercy, and then he let them go without any punishment. He spent most of his day lying in bed listening to his radio or reading the Quran, and never needed glasses to see. And though he didn’t like children much, he loved his own kids more than anything in the world. We later found a bunch of letters he wrote my mum after she had gotten married and moved to another country, telling her just because she had left his home didn’t mean she had left his heart. After my uncle was killed in that stupid war in the South, he stopped wearing cologne. I didn’t think he had the emotional capacity within him until I heard this story many years later.

He went to Umra every year, alone. When my grandmother, emotional and dramatic as always, would hold on to him crying in the airport because he was leaving, he would shake her off irritatingly, saying:

‘Khalas ya Zainab! Khalas! Mashi alakhra ana?!’ and storm off through the gates, and she would brush away her tears and injured pride and go back home, saying she shouldn’t have come to see him off in the first place (but not meaning it, and repeating the same scene the next year and the years after). During these Umra trips he sometimes had visions, and he told us that he dreamed he would live until the age of 95. He also dreamed that once he was walking towards a dark, fiery pit, and looked down to see thousands of people screaming in agony and terror, with huge, monstrous men carrying long whips looking over them. One of the men saw him, and told him that he was in the wrong place, and pointed in the other direction. He walked for a while until he came to a set of high golden gates, with the greenest green trees and plants flowing over the high walls. The man at the gate told him he was in the right place. But that he should go back because his time hadn’t come yet.

The dementia crept in slowly and stealthily, starting with just talkativeness, then forgetfulness, then sleep. After my grandmother died it went steadily downhill – a form of depression, it seemed. And then, one night he got up to go to the bathroom and tripped on the carpet and fell hitting his head on the ground. After that, he couldn’t walk properly, and when we went to the hospital we were surprised that there wasn’t a fracture anywhere, but that his kidneys had been failing for months, sending him into a deepening dementia. After that began the nightmare of 3 years, in and out of hospitals, surgery, dialysis, medications, and a worsening general condition. A nightmare that exposed the good and bad in everyone. Strangely, his dementia turned him into a different person; a quiet, peaceful, sweet little old man. Taking care of him was no more trouble than taking care of an obedient baby. He talked less and less, and then stopped talking at all. We prodded him with the story about Tayoba, and sometimes he would finish it, but eventually couldn’t. He gradually got smaller and smaller, and as his joints stiffened he lay permanently in the same fetal position he was born in. some nights he would call out in his sleep: to his children, dead and alive, his wife, his in-law friends. But most nights there was nothing. Sometimes he had nightmares and cried, but was easily reassured and went back to sleep. And then, on his 11thadmission since he first fell sick 3 years before, he coughed up a lot of phlegm and then just stopped breathing. He was exactly 95 years old.

And I wasn’t even there beside him.

In just a few hours, he was on his way through the desert, wrapped up in white and washed in perfume, carried towards his final resting place; the same place he came into the world as a baby. The oldest and last remaining son, who had outlived everyone but the 2 youngest girls. Prayed over, placed on the 3angaraib and lifted into the air, carried on alternating shoulders in a large silent procession moving on foot, out of the mosque that was hundreds of years old, where his ancestors had taught generations upon generations of boys and girls and men and women, towards the clean and organized graveyard to be laid down next to his brothers. A silent procession where everyone wore their 3immas on their heads except him. To be laid down in the dark, hot ground, where he couldn’t tell them if he was comfortable or not, to be covered with dirt and left alone in the dark, where he wouldn’t see another sun rise or set again. Returned to the same place he started: wrapped up with his knees up against his tummy, his right hand under his cheek, in the dark abyss of the in-between, with nothing but Allah’s great mercy and the Quran he spent his life reading to keep him company.

I wonder how he faced the end. Did he face it with his late, child-like fear? Or did he look it in the face, fire-stick in hand, ready and unafraid of anything? At least he knew where he was going, and I’m sure that whatever remained of his mind was confident and trusted in the God he spent his lifetime believing in and abiding by.

Goodbye, Mr. Fireman. سلم على امي زينب, tell her I’m sorry I didn’t come and visit but it was too painful for the first few years and then I couldn’t find her because the headstones were all messed up. وسلم على محمد خالي و على نِنِّس، , tell him that everyone’s lives fell to pieces after you left. And I’m sure that whatever place holds the four of you has to be some form of paradise, because that’s where people like you all go. I hope I see you again there, and maybe you’ll recognize me and remember my name. I’m sorry for not taking better care of you, but you left a void and now we don’t know what to do without you.

اعفي مننا وعافيين منك لله والرسول يا عصام الدين ولد سكينة، الله يرحمك ويوسع مدخلك ويكرم نزلك ويعوض تعبك الجنة، وكل اموات المسلمين، امين

الله يرحم الأستاذ عصام الدين ويجعل مثواه الجنة، من الواضح إنو سيرته العطرة مستمرة في أحفاده اللي إنت بتمثلي نموذج متميز ليهم. ربنا يصبركم

Thanks Hijazi

I've been remembering him a lot these past few days. Apparently the sadness gets worse before it gets better.

You took great care of him – the best. He couldn't have been blessed with better grandchildren, love and respect. May he rest in peace wa yajma3kum fi jannaat al na3eem.